The Phantasy Year of the Amazigh

Istambul · January, 2014, Ilya U. Topper

Assegwass Ameggaz! Happy New Year! Today and tomorrow you can hear this tamazigh phrase in many a home as well as outdoors in all regions of the Maghreb, from Cabilia and Melilla until Agadir and Warzazat. All over there you find people of Amazigh descend, a berber culture and language of thousands of years surviving after nearly a century of negation.

To celebrate openly the New Year in tamazigh has become a sign of revival of this cultural background. Incentives are not missing because this date is somehow characterizing the millennary patrimony of the Amazigh culture as part of world history.

But which date should be celebrated? January 13th or 14th? The greater part of the Amazigh outside Africa, mostly in France, Belgium, and Canada, but also in Spain, follow the tradition of Algerian Cabilia. They assure you that January 13th in the modern European calendar corresponds to the berber first day of the year. Most people don’t know why but simply follow this tradition.

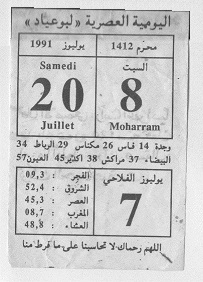

The Moroccan calendar called „fellahi“ or farming calendar in fact is the Julian Calendar still in use in orthodox Christian communities. Every Moroccan almanach – the ones you tear a sheet off every morning reading the pious phrase or a joke on its back – indicates three dates.

The first one is called the French, that is the afore mentioned modern European, or Gregorian, calendar, started by pope Gregor XIII in 1582 and followed by most Europeans since the 18th century, in Russia since the Revolution. The second date is that of the lunar Muslim calendar which in Morocco is merely used for religious holydays and observances like fasting (month of Ramadhan). It has only 354 days and thus is wandering all around the seasons in 33 years. The third one, the „fellahi“, marks the seasons according to the Julian sequence of days which today runs a fortnight behind the Gregorian one. So its first day falls on January 14th of the European one (see also our article „The calendar and Gregor’s reform” ).

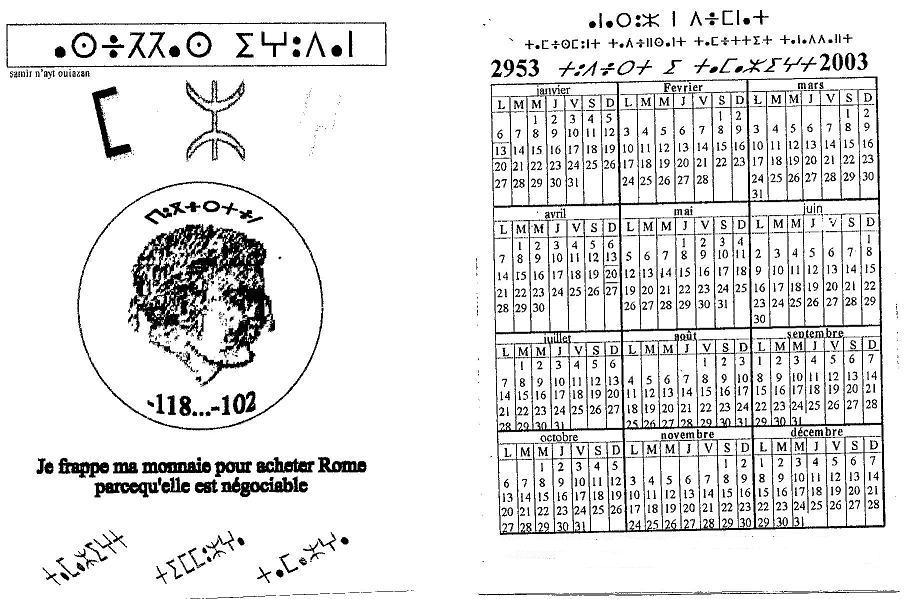

This „fellahi“ calendar is in use all over the Moroccan countryside and everybody knows that he has to add 13 days in order to comply with the citadine calendar. The rest is the same: length and names of the months: Yennayer, febrair, mars, ibrin, mayo, nunio, yulius, ghusht, shutamber, ktober, nowamber, dujanber, as well as the bisextile day on February 29th.

The Amazigh believe that this calendar was introduced by the Romans, by Julius Cesar, and is in use since then without interruption, so they follow it on account of their tradition. Conservation is one of their important elements, against all adversaries, even without organization or liturgy, and that is why they defend it proudly. They do not realize that some are misusing it and thereby destroy the innocent cultural heritage.

The problem was that unlike our calendar the Julian calendar does not count the years. It has no „era“. So an era was invented for them, probably by Europeans in France in the 1960s: the „era of Sheshonq“. Today we can read on posters: „Asseggwass Ameggaz 2964!“ Happy New Year 2964. But wherefrom comes this astounding number? They say that Sheshonq was an Egyptian pharao of Libyan origin, and that means: berber.

If you scrutinize this assertion you easily stumble on the simple explanation that somebody invented it without any foundation. Berber poeple don’t know about pharaos and their dates of life. They talk about Jedad u ben Ad, mythical ancestor of the Amazigh, the king who ruled men and jinn, lived for thousand years and was sovereign over many towns and lands. Solomon knew about him but could not say when he might have lived. (See Uwe Topper, Cuentos populares de los bereberes, Madrid 1988). No legend or myth ever gives trustworthy dates, if it does so it pertains to historiography.

Jedad uben Ad, mythical king of the Amazigh. Drawing by Uwe Topper

The base for the date of Sheshonq is European chronology of the Egyptian empires as founded by Howard Carter and colleagues, laboriously worked out and today accepted as consensus albeit with some small differences. Instead of 950 BC for the beginning of the reign of the said pharao scientists would now apply 955 BC, but everybody knows that this could change again.

It is remarkable that the descendants of a nation that is so securely anchored in the past that it conserved the Roman calendar without brake until today, want to bind their most authentic traditions to the juggle of European scholars. It appears that reinventing your own history and link your present to some long bygone past is the usual practice of nationalisms. To celebrate a year 2964 is not better than using any other number – e.g. „since the fall of the Lord of the Rings“, or any fantasy novel. It’s just a game. Yet, linking the Amazigh culture to such a paper deprives it of the authenticity it ostentates so far. Which in fact was appreciable: a culture that connects us with Roman tradition, not only by its calendar but by reminiscences of feasts, rites, and vocabulary, is a golden mine to retrieve our own history. And it ends when fantasy dates are incorporated.

This is not an exception. To reinvent your own history and make it by ancestral signs look like the oldest possible is habitual for all nationalisms. Of course, all eras of all calendars have been invented by the same manner: Nobody started counting the years from the birth of Jesus Christ. This began a millennium later when the birth of the Saviour was fixed to a certain date in the long ago past; nobody counted the years from the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem; no Roman began counting when the first walls of Rome were built, and likewise it was at least a century after the death of a prophet Muhammad when somebody thought it convenient to assign a date to that event in order to count the lunar years.

But to copy European egyptologists for an era Amazigh has neither style nor veracity. Why didn’t they call it „Year of Ad, mother of Jedad“?

If the extraordinary value of the Amazigh calendar should be conserved one would have to use it in its living form. Than January should begin on our January 14th, and not on 13th. Why this? It is the Gregorian calendar that omits three bisextile days in 400 years, namely in 1700, 1800, and 1900 (not so in 2000), so it runs ahead of the Julian one by one day every century. Between the 20th century and the 21st, New Year always falls on January 14th, but in the 19th century it equalled January 13th.

Now you can easily divine that the Julian calendar in Algeria came out of use after the French colonization in 1830. The tradition of the New Year remained fixed to the Gregorian date on January 13th, without anybody bothering about. The same thing happened in Turkey among the Kurdish people, as I was told: young men remember an important feast on January 13th but don’t know why.

This year important commemorations in Cabilia took place on January 12th, but it is unclear whether this was so because the eve before the feast is the moment to celebrate (just like in Europe New Year’s eve on December 31st) or whether eventually they follow a very old calendar that ended in the 18th century and could not be updated in 1900, although this seems unlikely. Confusion might be due to the practice of celebrating the eve. Nobody in Cabilia is aware that this day is bound to the old calendar because the „fellahi“ calendar is no longer in use there. To maintain the 13th of January is a dead alley and only reminds us of an old tradition tenacitely upheld since very long.

Example of a calendar of the Imazighen in Morocco for 2003 (with Gregorian day count)

(Translation by Uwe Topper)